Hunger is the most basic, the most primal, of human motivators. Hunger is what drew us out of our caves, drove us to hunt, to make tools, and build fires. Hunger has ploughed fields and raised revolutions. Hunger will get me out of a warm bed on a damp Sunday morning. Even the word, hunger, has become synonymous with ambition and determination, a steely grit.

I am deeply suspicious of a book which has no mention at all of food, or even the lack of food. A day in the life of a human being which didn’t include any food at all would be notable just for that. We all eat, and what’s more, the food we eat, even if it’s just a plastic-wrapped ham sandwich from a garage, tells a story about who we are. When we don’t eat, because we have lost our appetite, or refuse food in protest, or choose to abstain from food, or simply can’t get sufficient food, tells a whole other story.

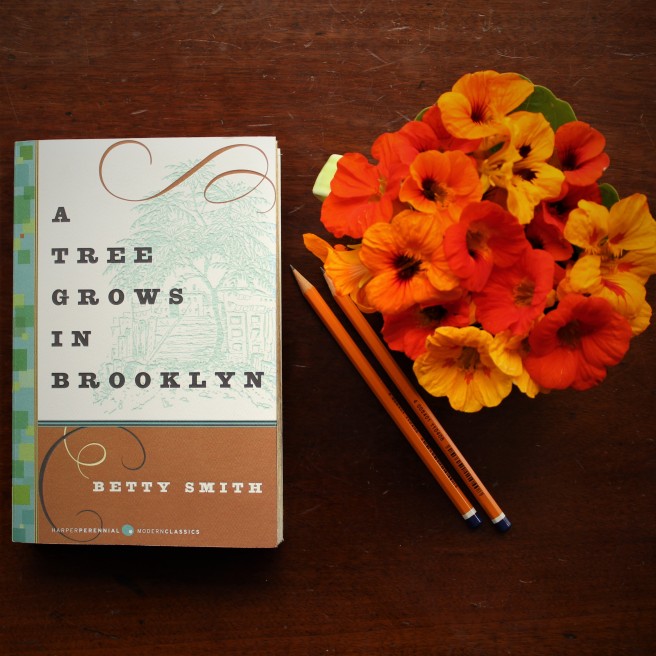

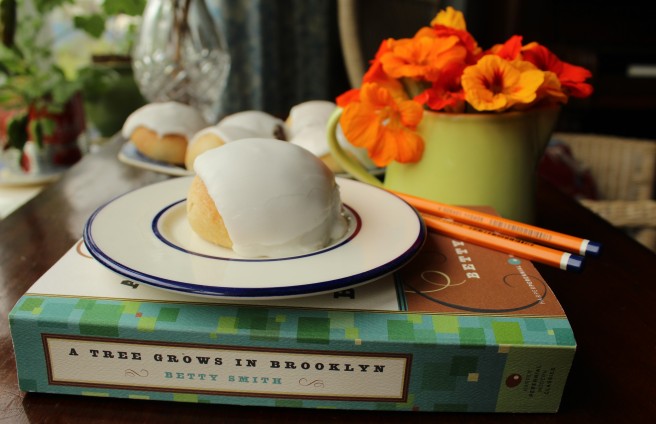

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith is a book all about hunger. It’s about wanting more. It is a book which reads like the truth, perhaps because it was, in fact, first written as an honest memoir but reconfigured as fiction at the request of an editor. From its first publication in 1943, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn was an instant bestseller. Almost 75 years later, this book remains relevant and inspiring and an absolute must-read. It is the story of Francie Nolan, daughter of Irish and German immigrants, growing up in the tenements of Brooklyn a century ago. It is a book about the trials of emigration, even to a land of dreams. It is about the reality, the daily struggle to get by, to push forward in the crush for cheap, day-old bread, and it is about the greater battle to carve out a more satisfying existence.

Just as Oliver Twist, “desperate with hunger and reckless with misery,” held up his bowl, Francie Nolan is a girl hungry enough to gather her courage and ask the world for more.

That there is more to be had, she knows because of her mother, Katie, and her mother’s mother, Mary Rommely. It is Mary who insists that Katie read to her children, a page every day from the bible and another of Shakespeare.

“You must do this that the child will grow up knowing of what is great – knowing that these tenements of Williamsburg are not the whole world.”

And it is Mary who, even though she can neither read nor write, appreciates the value of teaching children about fairies, elves and dwarfs, and ghosts and signs of evil and Kris Kringle.

“The child must have a valuable thing which is called imagination. The child must have a secret world in which live things that never were. It is necessary that she believe.”

These were women who saw the possibilities, women with enough imagination to see beyond the daily grind. But they were also practical, and brave, and relentless. They have devised dozens of ways to make a dinner from a stale loaf, Weg Geschnissen one day and fricadellen the next. They have saved pennies in tin cans and have imagined possibilities.

Where lesser women might have been content to merely put dinner on the table, Katie is committed to feeding Francie’s hunger.

“Look at that tree growing up there out of that grating. It gets no sun, and water only when it rains. It’s growing out of sour earth. And it’s strong because its hard struggle to live is making it strong. My children will be strong that way.”

Katie wants more for her children than money. She is appalled that they might turn out like the spoilt pub-owner’s child who throws candy down the gutter rather than share it with her neighbours. She knows there must be something more than money to escaping their world.

“Education! That was it! It was education that made the difference! Education would pull them out of the grime and the dirt.”

If Francie’s hunger, nursed by her mother and her grandmother, is for a bigger life, beyond the confines of working class Brooklyn, she knows instinctively that she will find it by the power of books.

There are people for whom words are almost as vital as food, people whose eyes scan constantly for things to read, people who will scavenge words wherever they can. Francie Nolan is one of those people.

“Francie was a reader. She read everything she could find: trash, classics, timetables and the grocer’s price list.”

The library is a shabby place, and the librarian unhelpful, but Francie thinks it is beautiful. She likes the librarian’s polished desk, likes the brown bowl filled with seasonal flowers, nasturtiums that day, clean blotter and the precise stack of library cards. Everything is neat, tidy, as it should be. This is the portal to the clean, bright future.

Francie has a plan: “She was reading a book a day in alphabetical order and not skipping the dry ones.”

Betty Smith’s references to food are subtle and yet fundamental to undertanding Francie’s drive and willpower. The very basis of the Nolan family’s being in America is rooted in starvation. Johnny Nolan, Francie’s Papa, is of Irish stock. His people “came over from Ireland the year the potatoes gave out.” Having been spared famine, Johnny has no ambition. He is a man of little substance, “a sweet singer of sweet songs” who hands over his meagre wages but keeps his tips for booze.

Johnny’s wife, Katie, knows that he’s sweet and useless; she is not bitter but often hungry.

Johnny’s fecklessness leaves the family literally on the brink of starvation. When Katie can’t buy food she invents a game in which she and the children pretend to be arctic explorers trapped by a blizzard, eek-ing out their rations and waiting for help.

All is forgiven when Johnny returns from singing at a wedding with a feast of someone else’s leftovers. Francie and her brother, who went to bed hungry, wake up in the middle of the night to a feast of lobster, oysters, caviar and Roquefort cheese.

‘They were so hungry that they ate everything on the table and digested it too, during the night. They could have digested nails had they been able to chew them.’

Eating all that food, it turned out, by the rules of the day and the Catholic Church, was a sin. Francie had broken the fast which should have lasted from mid-night until mass time. Keeping people hungry, of course, has always been an effective way to quell any bid for freedom. Francie learns that playing by the rules won’t get you what you want. She would gain her freedom even if she had to cheat a little, or lie once or twice and she would pay for the lies with her pride.

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn details the gradual unravelling of innocence, the end of a childhood and awakening of an intelligent, determined young woman. Betty Smith peels back the veil on ordinary lives, like opening the front of an old dollhouse. She lays bare the truth of her own youth in a series of intensely detailed vignettes. The reader is left with the feeling of being trusted with a confidence; it is a sensation almost of privilege. If you one of those people who craves books and feeds on the written word, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn will leave you with a warm glow of satisfaction.

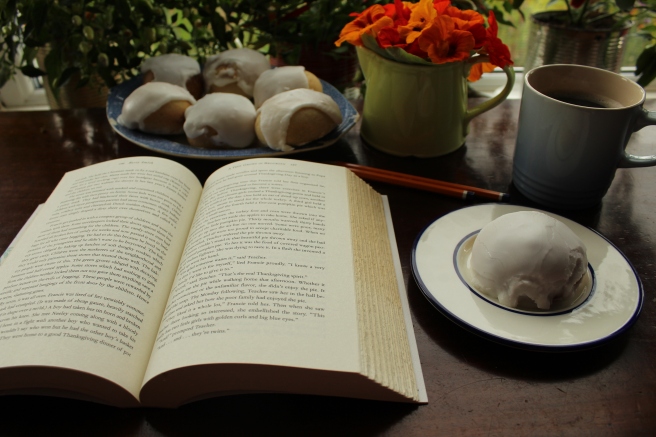

Sugar Buns.

When things are good, when Papa stays sober enough to hold down a job and the Nolan family gets a stab at happiness, when they have more to eat than a variety of meals concocted from stale bread, they eat sugar buns. From their first happy married days, when they worked together on a night shift, Katie and Johnny loved arriving home to have ‘a breakfast of hot coffee and warm sweet buns.’ The piano teacher is paid in house-cleaning services, and an agreement to have coffee and a sugar bun at the end of every lesson.

When Katie feels secure, she gives Francie the five cents that might have gone to the tin can of savings and says instead,

“All right. Get the buns.”

Francie takes her time choosing four buns, the ones with the most sugar on top.

Each member of the Nolan family was allowed a cup of hot coffee from the pot. Katie considered the coffee a worthwhile indulgence. What’s more, Francie was permitted to simply cradle the warmth of her coffee, if that was what made her happy, and then throw it down the sink.

‘I think it’s good that people like us can waste something once in a while and get the feeling of how it would be to have lots of money and not have to worry about scrounging.’

Waste not, want not is the doctrine of those who must make do with what they have. Katie understood the value of wanting more. The sugar bun is a treat but also serves to make Francie aware of the possibilities.

“The girl felt that even if she had less than anybody in Williamsburg, somehow she had more. She was richer because she had something to waste. She ate her sugar bun slowly, reluctant to have done with its sweet taste, while the coffee got ice-cold.”

Life won’t, and can’t, be all sweet buns, but when you get one, I suggest you make a pot of good, strong coffee and take the time to relish it.

Ingredients.

1 lb (450g) strong bread flour

½ tsp salt

1 oz (30g) sugar

1 packet (7g) of easy-action dried yeast

2 oz (60g) butter

½ pint (275 ml) milk

8 oz (225g) icing or confectioner’s sugar

1 lemon

Method.

Mix the flour, sugar and salt and yeast together in a large bowl.

Melt the butter. I place it in a glass measuring jug and melt it in the microwave. Add the milk to the melted butter. The milk and butter combined should be close to blood temperature – such that you can dip your pinkie finger in and it will feel neither hot nor cold. You may need to heat it a little more to reach this point.

Add the wet ingredients to the dry and mix to combine into a rough ball.

Turn the dough on to flour-dusted surface and knead it, stretching it away from you with the heel of your palm and drawing it back into a ball. Turn it, stretch it, pull it, push it, give it a bash…you won’t find any better therapy. Continue to knead for at least eight minutes by which time the dough should feel more elastic. It should spring back if you press your thumb into it and have a silky appearance.

Place the dough in a greased bowl. Cover it with a tea-towel or, more effectively, a shower cap. Leave it in a warm place to rise for about two hours.

Now, the best part: take your risen dough and use your hands to knock the puff out of it. You don’t need to knead it again. Divide the dough into eight pieces. Take each of these pieces in turn and form them into round buns by rolling them around between your palm and the work surface. Use a tucking under action to smooth the surface of each bun.

Place the buns on an oven tray, cover them again with a cloth or cling film, and leave them in a warm place for an hour or so until you can see that they have risen up.

Brush each bun with a little milk and bake in an oven pre-heated to 200˚C for 20-25 minutes. They should have a golden colour.

While the buns cool, mix the icing sugar with enough lemon juice to make a fairly stiff paste. This should take the juice of half a lemon, maybe a little more. Spread this icing over the buns and allow it to harden.

While you wait, make the coffee.